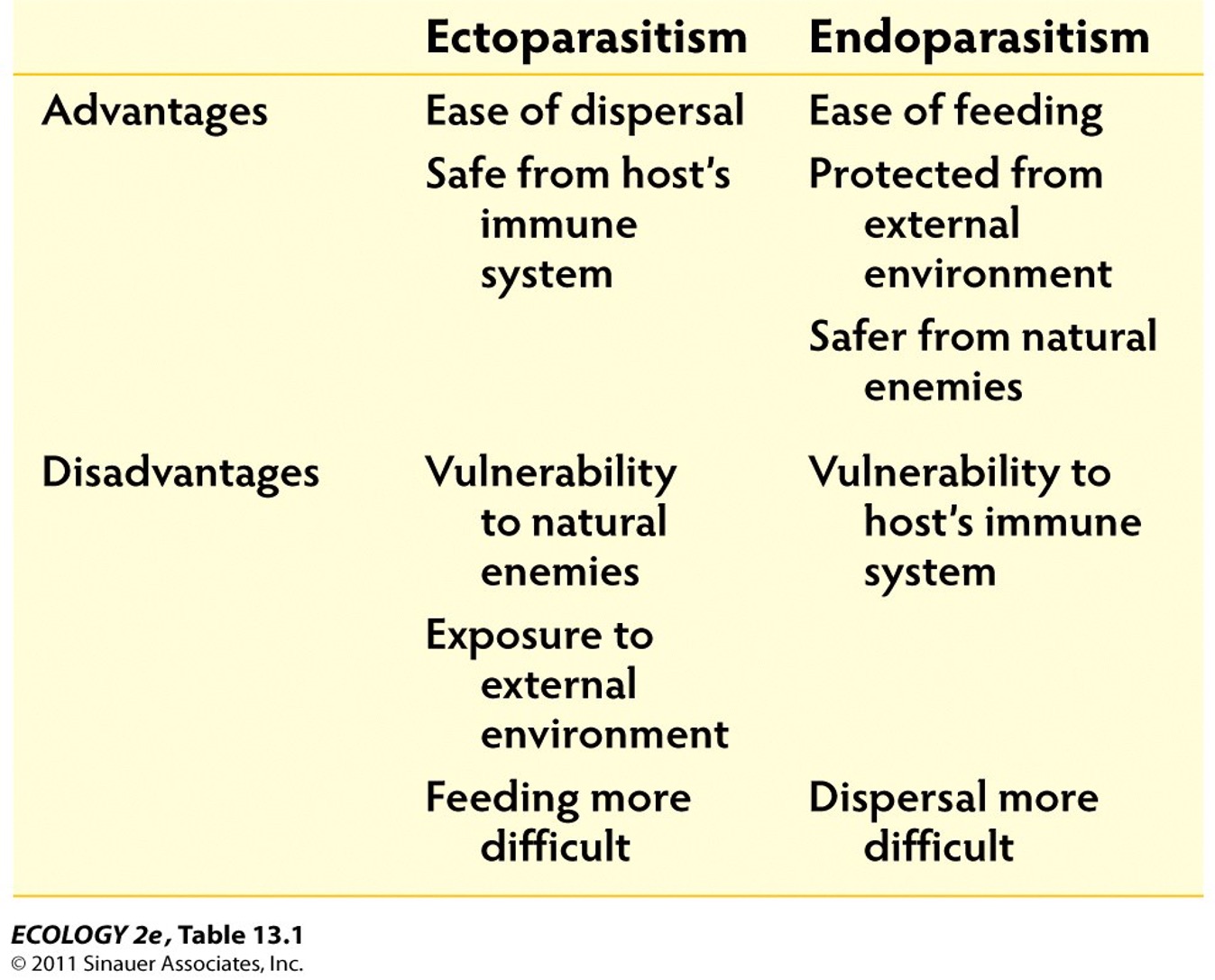

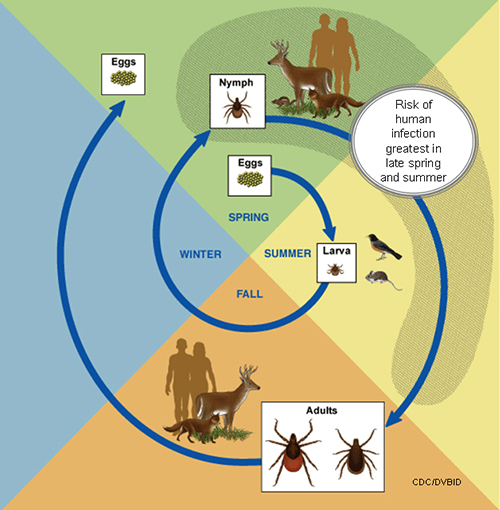

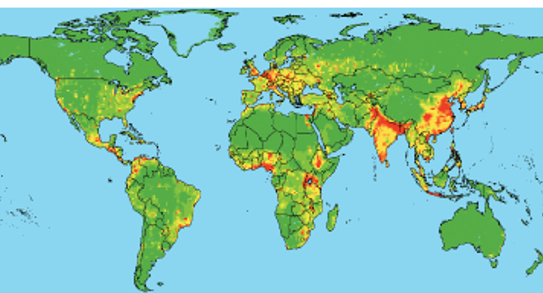

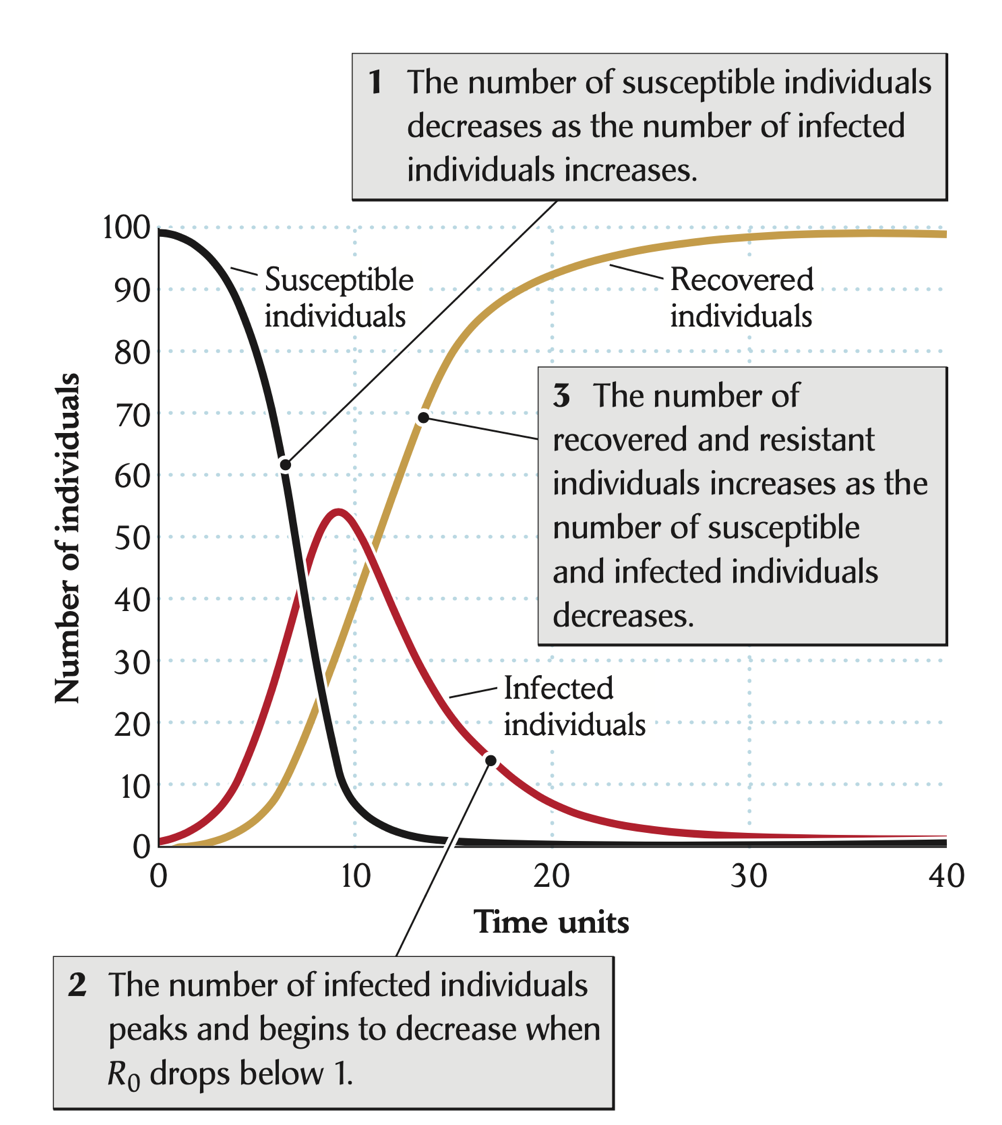

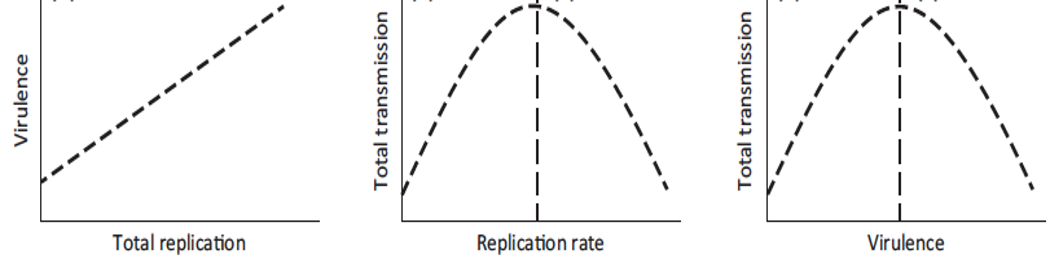

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Host-parasite interactions ] .author[ ### Daijiang Li ] .institute[ ### LSU ] --- class: left, middle class: left, center, inverse .font300[Announcements] + .font200[Final project!!] + + --- background-image: url('figs/covid.png') background-position: 50% 50% background-size: contain class: center, middle, inverse # .font200[Pandemic] --- # Parasite-Host Interactions .font200[ 1. Effects of parasites 2. Types of parasites 3. Modeling parsite-host interactions 4. Parasite-host coevolution 5. Disease spread ] --- class: center, middle .pull-left[  ### Zombie Movies ] -- .pull-right[  ### [Zombie in nature: article](https://www.wired.com/2014/09/absurd-creature-of-the-week-disco-worm/) ] --- class: middle, center <iframe width="1200" height="498" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/Go_LIz7kTok" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe> --- # Parasite, pathogen, infection, and disease .font200[.red[parasite]: an organism that lives in or on another organism (.green[host]) and causes .blue[harmful] effects (sometimes suffering, even excruciating misery, but not _immediately_ causing death) as it consumes resources from the host.] .font150[(consumer-resource)] -- .font200[When parasites colonize a host, that host is said to harbor an .red[infection]] -- .font200[Only if that infection gives rise to symptoms that are clearly harmful to the host should the host be said to have a .red[disease], e.g., COVID-19] -- .font200[.red[Pathogen]: any parasite that causes a disease (i.e. is ‘pathogenic’), e.g., SARS-CoV-2] ??? though infection by a pathogen does not always result in an infectious disease; asymptomatic --- # Parasites are diverse ### Pretty much every organism of living thing has one or more parasite, including parasites (_hyperparasite_) -- ### Many parasites are host-specified or at least have a limited range of hosts (_specialists_); few has a broad range of hosts (_generalists_) -- ### The conclusion seems _unavoidable_ that .red[more than 50%] of the species on the earth, and many more than 50% of individuals, are parasites --- # Effects of parasites ### Large toll on people: >25% human deaths are caused by infectious disease; 100 million people died in 1918 (the Great Influenza Pandemic caused by H1N1 virus); >6 million deaths caused by COVID-19 so far ### On wildlife: bird flu; chytrid fugus caused extinctions of amphibian species; white-nose syndrome for bats ### On plants: crops (e.g., wheat rust), trees (e.g., chestnut blight, dutch elm disease) ??? american chestnut trees used to be >50% of trees in temperate forests; now they are rare since the introduce of chestnut blight around 1900 from Asian --- # Types of parasites .font130[ - By location + .blue[ectoparasites]: live on the outside of organisms (e.g., ticks, mites, lice, fleas, mistletoes) + .blue[endoparasites]: live inside organisms (e.g., virus, cestode), often cause diseases ] .center[] --- # Types of parasites .font130[ - By location + .blue[ectoparasites]: live on the outside of organisms (e.g., ticks, mites, lice, fleas, mistletoes) + .blue[endoparasites]: live inside organisms (e.g., virus, cestode), often cause diseases ] .font130[ - By size + .blue[microparasites]: small and often intra-cellular, reproduce directly within host and are often extremely numerous (e.g., virus, some types of bacteria and protists) + .blue[macroparasites]: larger, live on or within a host (in cavities such as the gut or inter-cellular), do not reproduce in their host (e.g., helminth worms in an intestine, some types of fungi, bacteria and protozoa) ] -- .font130[ - By transmission mode + .blue[horizontal]: move between individuals other than parents and offsprings + .blue[vertical]: transmitted from a parent to its offspring ] ??? tradeoffs: exposure to natural enemies, external envi, difficulty to move among host, ease of feeding on hosts --- # Why be a parasite? .pull-left[ ## It’s a Beautiful Life! .font200[ - Your host does it all: - Searches for food! - Escapes Danger! - Makes a cozy, steady environment! ] ] -- .pull-right[ ## The Result: .font200[ - Bathed in Ambrosia! - No need for limbs, most organs, etc… - All you really need to do is suck up nutrition and reproduce! ] ] -- ### BUT – if being a parasite were _that easy_, we would all be … --- # Challenges to the parasitic lifestyle .pull-left[ .font150[ 1. Host defenses 2. Successfully finding the right host: Hosts are usually: - Bigger than you, but, - Much more mobile, and - Pretty sparse. ] ] .pull-right[ ### All of this selects for: .font150[ 1. Adaptations to maximize a complete life cycle: Getting yourself or your progeny back to the right host 2. In particular, Complex Life Cycles: choose hosts that will tend to encounter one another or put you in the right place at the right time. ] ] --- # Hosts as habitats .font130[Hosts as reactive environments: resistance, recovery, and immunity] .center[  ] .font130[Chimpanzees infected with nematodes seek out and eat a bitter plant that contains chemicals that kill or paralyze the nematodes: Self-medication is not just for humans] ??? A universal pharmacy: Possible self-medication using tree balsam by multiple Atlantic Forest mammals https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/btp.13095?af=R --- class: center # Parasite life cycle complexity  ??? Stage 1: Egg Tick eggs are often laid in the spring after female ticks complete their two to three-year life span. Eggs are often brown and red in color and appear to be translucent. One tick can lay thousands of eggs. While ticks need to detach before laying eggs (and therefore can’t lay eggs directly on a host), eggs can be found under leaf litter, leaf brush and other warm, soft places outside. Stage 2: Larva In the summer, tick eggs hatch into six-legged larvae. Although rare, larval ticks may be infectious as some tick-borne illnesses can be transmitted from an adult tick to the eggs, which is called transovarial transmission. However, ticks mainly become infectious once they absorb a pathogen from one of their hosts. For example, during the larvae stage, one of the most common tick host is the white-footed mouse, a mammal which is known to carry Lyme disease causing bacteria (Borrelia burgdorferi). The white-footed mouse is also referred to as the reservoir host of Lyme disease, meaning that this mammal is able to transmit the bacteria to a feeding tick. If instead, the larvae feed on other hosts like racoons and squirrels which are not capable of transmitting the disease, the larvae will not yet become infectious. If a larval tick becomes infected with Lyme disease or another tick-borne illness, they will maintain the infection throughout the remainder of their life which is referred to as transstadial transmission. When the larvae are finished feeding on their first host, they’ll fall to the ground and begin molting as they transition to the next lifecycle stage – nymphs. Stage 3: Nymph Between the fall and spring, larvae will molt into nymphs. At this stage, they have eight legs and are most active when the weather is above 37 degrees Fahrenheit (though tick checks should still be performed year-round when traveling through known tick areas). During the colder months, nymphs will sit dormant under leaf litter, snow cover and shaded areas. When the weather warms, nymphs will begin questing behavior in order to locate their next host. If already infected, nymphs can transmit Lyme disease to their new host, or nymphs may become infected with a tick-borne disease by feeding on an infected reservoir host, or even contract a second tick-borne disease making them co-infected with various pathogens. In fact, since April 2019, 7,002 Nymph Blacklegged Ticks were tested for Lyme disease and a total of 31.1% (2,177) tested positive. Find more Tick Testing Data and statistics here – https://www.ticklab.org/statistics. Once attached to their host, nymphs will feed for four to five days before dropping off to start transitioning into their final life stage – an adult. Stage 4: Adult During the fall, when the nymph falls off its host and transitions into an adult, it will look for its third and final host. During the nymph and adult phases, ticks can seek out humans as their hosts and possibly transmit disease(s). In fact, in Pennsylvania, one out of every two Adult Female Blacklegged (Deer) Ticks are infected (45.4% carry Lyme Disease; 17.4% carry Anaplasmosis; 2.8% carry Babesiosis; and 1.1% carry Powassan Virus). Although the prevalence of tick-borne illnesses can range upwards of 65% in some counties of PA, transmission from tick to host can vary from as fast as 15 minutes for Powassan virus to 36-48 hours for Babesiosis. Lyme disease transmission can occur as early as 18-24 hours of a tick being attached to a host. During winter, adult ticks unable to locate hosts retreat underneath leaf litter or other surface vegetation, becoming inactive in temperatures below 37 degrees Fahrenheit. With the exception of unusually warm winters, adult ticks will begin to become active again in late February / early March, when they will resume their quest for a bloodmeal. After feeding on their final host, and depending on the weather and time of year, ticks will look to begin mating. Males typically die after mating with a female, and females will reproduce by laying thousands of eggs during the spring and die shortly thereafter, thereby completing the tick lifecycle. Always remember to keep a lookout for ticks at each stage of their lifecycle so you’re best equipped to avoid tick bites and to protect yourself, your family, your friends and pets. --- # The parasite niche ### Multidimensional space of tolerances and requirements of a species (abiotic and biotic) ### Niche --> understand and predict geographic distribution ### Niche --> understand host range and predict host switching; .blue[_spillover_] if the host switching involves the ability to infect a human host .font130[ - the Great Influenza Pandemic in 1918 (H1N1 virus from birds) - HIV (virus from chimpanzees) - SARS in 2003 (SARS-CoV from bats?) - COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2 from ?) ] --- class: center # Spillover Hotspots  Jones et al. 2008. Nature. 451:990 .font150[Emergence of zoonotic diseases from bringing human beings into closer contact with reservoir species] --- # The consequences of host reaction: S-I-R ## .red[S] : susceptible individuals ## .red[I] : infectious individuals ## .red[R] : recovered (and immune) individuals ### .blue[Costs of parasitism don’t have to involve death.] --- # S-I-R model .pull-left[ .font150[ `\begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} & = -\beta SI \\ \frac{dI}{dt} & = \beta SI - dI \\ \frac{dR}{dt} & = dI \end{align}` ] ] -- .pull-right[] --- # S-I-R model .pull-left[ .font150[ `\begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} & = -\beta SI \\ \frac{dI}{dt} & = \beta SI - dI \\ \frac{dR}{dt} & = dI \end{align}` ] ] .pull-right[ ## Model assumptions .font150[ - A well-mixed population - Same susceptibility for every individual - No births of new susceptible individuals - Permenant immunity after recovering ] ] --- # `\(R_0\)` .pull-left[ .font150[ `\begin{align} \frac{dS}{dt} & = -\beta SI \\ \frac{dI}{dt} & = \beta SI - dI \\ \frac{dR}{dt} & = dI \end{align}` ] ] .pull-right[ .font150[ `\(\frac{dI}{dt}>0\)` only if `\(\beta SI > dI\)` `\(R_0 = \frac{\beta SI}{dI} = \frac{\beta S}{d}\)` `\(\frac{1}{d}\)`: the average duration of infection ] ] -- ### `\(R_0\)`: .green[the number of secondary infections generated by a single infected individual in a wholly susceptible population] ### It provides a powerful framework for exploring the dynamics and control of epidemics --- # `\(R_0\)` of COVID-19 by 23 May, 2020 <img src="figs/r0_usa.jpeg" width="95%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Ives and Buzzuto, 2021 https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-020-01609-6 --- # How do we reduce `\(R_0\)`? .font200[$$R_0 = \frac{\beta S}{d}$$] .pull-left[ .font150[ - `\(d\)` ? - `\(\beta\)` ? - `\(S\)` ? ] ] -- .pull-right[ .font150[Vaccination: what fraction of population to achieve _herd immunity_?] `\(R_0 = \frac{\beta S (1 - c)}{d} < 1\)` `\(c > 1 - \frac{d}{\beta S} = 1 - \frac{1}{R_0}\)` ] -- ### If `\(R_0\)` of COVID-19 is 4, that means we need to vaccinate 75% of population to control the pandemic --- # Evolution of host-parasite systems ### Natural selection has favored the evolution of .red[parasite offenses] and .blue[host defenses] ### Parasite should optimize the trade-off between virulence and transmissibility (Ebola – highly virulent but not highly transmissable)  ??? First, increasing within-host parasite replication increases virulence (A); second, increasing within-host parasite replication increases the number of parasite transmission events over the duration of the infection (B), until a point where increasing parasite replication reduces the infectious period (e.g., by killing the host and preventing transmission) (C); and third, increasing parasite virulence increases parasite transmission (D) until high virulence shortens the infectious period, thereby reducing transmission (E) --- # Evolution of host-parasite systems ### Natural selection has favored the evolution of .red[parasite offenses] and .blue[host defenses] ### Parasite should optimize the trade-off between virulence and transmissibility ### Hosts also evolve, but typically slower than parasites, producing arms races between hosts and parasites ### The .red[Red Queen Hypothesis] predicts a continuing evolutionary battle between parasites and hosts, not a stable equilibrium --- # Evolution of host-parasite systems: rabbits and myxoma virus <img src="figs/rabbits.jpg" width="60%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> > .font130[The wild rabbits started to resist the virus, the virus started to kill them in a new way, and neither side gained any ground. “It’s like a duck in a stream, paddling like crazy under the water and not getting anywhere,” says Read.] [The Next Chapter in a Viral Arms Race](https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/08/rabbit-virus-arms-race/536796/) [Next step in the ongoing arms race between myxoma virus and wild rabbits in Australia is a novel disease phenotype](https://www.pnas.org/content/114/35/9397) [Seventy years ago, humans unleashed a killer virus on rabbits. Here's how they beat it](https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/02/seventy-years-ago-humans-unleashed-killer-virus-rabbits-heres-how-they-beat-it) ??? In 1859 European rabbits were introduced to Australia, exponential growth of rabbits In 1950, the government released a virus known as _Myxoma_ to control rabbits. It kills an infected rabbit in 48 hours, with 99.8% killing rates. Second breakout: 90%; third breakout: 40-60%; ... 6th breakout: 20% rabbit populations rebound, virus persist --- # Disease spread ## Environmental controls disease spread .font200[ - Environment influences transmission process - Environment affect the growth of pathogen within a host and the host - Environment affect host or vector behavior + Host behavior: social contact networks ] --- # Global environmental change and disease spread .font200[ - Land use change - Climate change - Species invasion - Community composition and biodiversity ] --- background-image: url('figs/covid.png') background-position: 50% 50% background-size: contain class: left, middle, inverse ## .red[How does this lecture help you in] ## .red[understanding the current pandemic?] --- class: middle, left .font200[ In the SIR model, if S is 99 and I is 1 (total population is 100) at the beginning of a disease infection, which has R0 of 3 and average infectious period of 7 days. What is the transmission rate (beta)? A. 0.1 B. 0.2 C. 0.004 D. 2 ] --- class: middle, left .font200[ If transmission rate is 0.5 and recovery rate is 0.3, what is the herd immunity threshold (let S to be 1)? A. 0.15 B. 0.57 C. 0.40 D. 0.78 ]